Reconciliation as Activity: Constraints and Possibilities

Ivor Sokolić and Denisa Kostovicova, London School of Economics and Political Science

Reconciliation is proving to be a problematic concept for both practitioners and academics: it is laden with normative expectations and is often rejected by local publics. Ivor Sokolic and Denisa Kostovicova report on the exchange with civil society in Kosovo on reconciliation as activity. Participants shared their experiences of how interethnic contact between individuals through a variety of activities often had unintended positive outcomes for intergroup relations.

On 05 March 2018 the London School of Economics and Political Science, as a part of the ‘Art and Reconciliation: Conflict, Culture and Community’ project (artreconciliation.org), held a collaborative workshop in Prishtina titled “Activity as Reconciliation: Lessons from Practice”. The event was organised together with our local partner in Kosovo, the Centre for Research, Documentation and Publication (CRDP), who work on, and research, themes of peace, justice and truth in Kosovo. There was considerable overlap with the CRDP’s work on human security and reconciliation and our own, which made for a natural partnership for the workshop organisation. The workshop was attended by representatives of local and international civil society organisations who conduct a range of activities within communities and across ethnic lines. Some dealt directly with reconciliation issues (for example, efforts in coming to terms with the past), but many did not (for example, youth dialogue programmes).

The workshop dealt with one of the key research questions behind the AHRC-funded project, ‘Art and Reconciliation’: how to reconceptualise reconciliation? Our partner’s findings on reconciliation show the importance of this question in the post-conflict context in Kosovo. They find that projects under the label of reconciliation were initiated too early, are simultaneously both unclear and too ambitious, and favour one side of the conflict (the full results can be found here). This has often resulted – mirroring experiences in other post-conflict contexts – in the rejection of the concept on normative grounds. The biggest challenge, then, is how to reconcile this rejection with the necessity, as well as the desire expressed by many who themselves have suffered from violence, to work on social repair for the sake of peace.

The workshop addressed this conundrum by reframing reconciliation as activity. The premise here is to focus on activities that, sometimes labelled as reconciliatory and sometimes not, lead to better relations between groups. Underpinning this was the idea that activities that involve contact between different groups – be it physical or symbolic (such as interaction with outgroup symbols), intentional or unintentional – can lead to positive outcomes for intergroup relations. Many of these activities are missed in traditional appraisals of reconciliation, which are loaded with specific expectations of what the process and outcomes ought to look like. This focus on activity, then, helps to reconceptualise and critique reconciliation. Together with civil society organisations, we shared experiences of what types of activity can aid reconciliation and what is it about these types of activity that make them conducive to transforming interethnic relationships. We questioned if this concept was useful, and if not, what concept would be more useful from a practice-oriented point of view?

Representatives of civil society exhibited a readiness to acknowledge the problems associated with the normative load of reconciliation, which had become an impediment to the work they were undertaking. Some felt trapped, since they needed to adhere to labels to attain funding, but these labels hampered their work. Organisations experienced hostility towards their work, if they labelled it as reconciliatory. At the same time, numerous examples were provided of activities they had undertaken that had positive outcomes on intergroup relations, but which did not fall under the label of reconciliation. Participants also noted a number of macro and micro factors that inhibited these types of activities from taking place. Three key themes, with clear policy implications, underpinned the discussions on the day.

Structural barriers to activity

First, the structural dimension of activities that can aid, or hinder, reconciliation was highlighted. On the macro level, dynamics between the global and the local; donors and civil society organisations; and civil society and the state, all defined the structural framework within which organisations operated, and by which they were often constrained. The ghettoisation of minorities, segregated educational systems and regional divergence in state capacity within Kosovo made it easier for organisations to conduct activities between Kosovo Albanians and Serbs from Serbia, rather than with Kosovo Serbs. These macro level differences also fed into other issues. Differences in education provisions meant participants noted that the language barrier between Serbs and Albanians, who do not speak each others’ language, which is often seen as an intrinsic barrier to cooperation, could be overcome through the shared understanding of English. This was, however, found to disadvantage Kosovan Serbs who lacked sufficient English skills to communicate with Albanians. An inability to communicate within Kosovo thus forecloses opportunities for reconciliation even when reframed as activity.

Generational focus of activity

The generational dimension, with an emphasis on youth and the transgenerational dimension of reconciliation, was the second key theme underpinning discussions. Many civil society organisations targeted their work at young people and saw positive outcomes between groups. These organisations defined success in their work as educating young people about opportunities to travel, to converse with other groups and, sometimes, as enabling such travel and exchanges. They believed these activities provided participants with new information that questioned dominant narratives about the conflict, as well as an invaluable opportunity to meet members of the other ethnic group. These situations did not involve discussions about politics, society or violence at first, but through socialisation outside of the core activities of travel or exchanges (for example, over drinks) and in the pursuit of common interests (for example, interests in the arts or music), these conversations began to occur. They “talked about the war incognito”. This finding contradicts the commonly assumed premise that the divergent, ethnically-centred, representations of conflict are an obstacle to discussions about the most delicate issues concerning the conflict. In this respect, activities that are not primarily addressed at reconciliation, through challenging dominant narratives about the conflict, facilitate exchange on the most challenging issues dividing Serbs and Albanians.

Formal resistance to reconciliation

Much of the activity with positive intergroup outcomes that organisations had undertaken occurs in the informal domain, which emerged as the third key theme of the day, but these processes meet resistance from formal institutions and societal norms. Informality, across all levels of society, was seen as a space where friendships were created. The informal spaces at the margins of reconciliation efforts contained some of the most meaningful interactions between groups. They were spaces where constraints surrounding interaction across ethnic lines disappeared. Civil society organisations believed there was a readiness to reconcile, observed through informal activities that resulted in restoration of torn relations between members of the two communities. This trend was also documented in the LSE-based research (available here), that found that Albanians’ and Serbs’ participation in Kosovo’s informal economy that cuts across ethnic lines leads to creation of friendships, and was reflected in the above-mentioned study by the CRDP (available here). The positive will to change was, however, obstructed by societally defined boundaries that formal institutions reproduce. Organisations cited examples of cultural programmes, exchanges or interethnic sports events that were literally halted by politics. They also highlighted the reproduction of ethnic division through textbooks, nationalist political rhetoric and the political instrumentalisation of minorities. The effect was that individuals often made friends with members of the other ethnicity in the informal setting or away from their home or in spaces where they would not be exposed to public scrutiny, only for these interactions to be sanctioned by their own ethnic communities.

Summary

Overall, the workshop provided a forum for dialogue based on evidence deriving from academic research and experience from practice focused on reconceptualising reconciliation as activity. This recognised the paradox of people’s desire and need for normalisation of relations, dignity and reckoning with the legacy of conflict and the hostility towards the concept of reconciliation. The resulting outputs will be both academic publications (including a journal special issue edited by I. Sokolić) and a policy brief for local and international policy makers. The policy suggestions will focus on the roles of education, youth and cultural activities. Improved English language teaching across ethnic lines can provide a lingua franca for future generations. Youth exchange projects will be recommended since they are cost-effective and not typically labelled as reconciliatory. Furthermore, activities in the cultural sphere, such as the arts, will be highlighted due to their potential to help younger generations from different ethnic groups meet each other and bond over shared interests.

1919 we had shifted to building hundreds of military cemeteries where every single soldier, down to the lowest Private, would be eternally remembered, in stone like a pharaoh. Elaborate ceremonies – this thing we call ‘Remembrance’ with a capital R – were manufactured to memorialise their deaths. The sheer number of dead and the brutal, industrialised meaninglessness of their dying called forth the greatest period of British cultural creativity of which you’ve never heard. This lecture (which is based series of documentary programmes) examines how that change came about and offers a hard-hitting polemic against the standard model of Remembrance that was created after the Great War. What’s wrong with pretty war cemeteries and cenotaphs and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier? Quite a lot, this lecture argues.

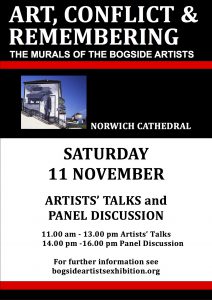

1919 we had shifted to building hundreds of military cemeteries where every single soldier, down to the lowest Private, would be eternally remembered, in stone like a pharaoh. Elaborate ceremonies – this thing we call ‘Remembrance’ with a capital R – were manufactured to memorialise their deaths. The sheer number of dead and the brutal, industrialised meaninglessness of their dying called forth the greatest period of British cultural creativity of which you’ve never heard. This lecture (which is based series of documentary programmes) examines how that change came about and offers a hard-hitting polemic against the standard model of Remembrance that was created after the Great War. What’s wrong with pretty war cemeteries and cenotaphs and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier? Quite a lot, this lecture argues. he Bogside area of Derry, Northern Ireland. For more information see

he Bogside area of Derry, Northern Ireland. For more information see