Nora Biette-Timmons reflects on the public lecture ‘After the Hague Tribunal: prospects for justice and reconciliation in the Balkans’, which took place on Thursday 3 May 2018. The event was organised by the Conflict Research Group, which is based within the LSE Department of Government, and the Arts and Reconciliation research project.

Last November, in a courtroom in The Hague, former Bosnian Croat general Slobodan Praljak downed a vial of poison upon hearing that the International Criminal Tribunal (ICTY) had upheld his 20-year prison sentence for crimes against humanity and Geneva Conventions violations. The story, which made international news, was historic for many reasons, not least its shocking conclusion. The ruling in Praljak’s appeal also marked one of the final decisions of the Hague Tribunal’s nearly 25-year run.

The ICTY wrapped up proceedings in December, and now regional observers are treading water, waiting to see what comes next. A panel of experts convened at LSE earlier this month to discuss the tribunal’s mixed legacy, and what challenges the former Yugoslav countries face in its aftermath.

Though the Balkans conflict broke out more than three decades ago, one of the primary issues plaguing its aftermath is a problem all too familiar in 2018: “alternative facts” and a fundamental disagreement on what exactly happened.

The ICTY was supposed to aide this process of agreeing upon the historic record. According to panelist Eric Gordy, Professor of Political and Cultural Sociology in the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at University College London, the point of the court was “to use the process of presentation and discussion and contestation and presentation of evidence to establish facts.” However, the tribunal’s narrow scope, the general public’s relative indifference to its proceedings, and national governments’ criticisms of its rulings exacerbated the court’s already-limited ability to cultivate a widely accepted set of facts.

As Jelena Subotic, Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at Georgia State University, put it, the court’s jurisdiction was hyper specific: It was “prosecuting a very small subset of individuals in what were mass crimes done by groups against groups,” she said. The cases it tried were “not about what happened in Bosnia… Rather, they were about what happened in this particular village in Bosnia in 1993.”

Despite this, James Gow, Professor of International Peace and Security in the Department of War Studies at King’s College London, noted that the ICTY was important in giving at least victims a platform to tell their stories and be recognized by the international community.

Perhaps because of that specificity, the tribunal’s mission and the legacy of the war appear to be less relevant to the region’s nation groups today. “The situation is worse now than it was 15 to 20 years ago,” said Jasna Dragovic-Soso, Senior Lecturer in the Department of Politics and International Relations at Goldsmiths University of London. “At the end of the tribunal’s existence, fewer people state that they know the tribunal’s purpose or about the crimes [it tried], even if crimes were committed against their nation group.” In addition, like much of the West, the Balkan region is facing a resurgence of nationalism. The consequence, Dragovic-Soso said, has been a rise in “crimes that suggest nostalgia” and ignore the horrific results of nationalist crime in the 1990s.

And rather than facilitating any sort of resolution, the tribunal’s rulings — even in these discrete cases — often prompted national groups to double down on the innocence of their countrymen.

Croatian reaction to Praljak’s sentence and subsequent suicide reflected this intractability. In a press conference a few hours after the incident, Prime Minister Andrej Plenkovic said Praljak’s act was caused by the “deep moral injustice” exercised against Croatian nationals convicted in the ICTY. Plenkovic condemned the court’s broader legal legacy, characterising its failure to establish “the responsibility of Serbia’s leadership for involvement in a joint criminal enterprise” as “absurd.”

Beyond the ICTY, these nationalist reactions frustrate a need for what Subotic calls societal responsibility. “The state can provide official apologies and reparations,” she said, but permanently changing the minds of nation groups has proved to be a more difficult task.

“Why is it so hard to admit that crimes were done by your group to another group? Why does that minimise your group’s suffering?,” Subotic asked. “Why is it so difficult to acknowledge and provide some kind of redress for horrific crimes that were done with your tax money?”

Subotic’s “dream” example of societal responsibility would resemble the “Berlin millennials who go to publicly available archives to see who lived in their apartments previously. They want to mark who lived in the apartment and where they were taken. That is societal responsibility.”

Such developments would first require an archive, and establishing one is of great importance for many in the region.

Some of the panelists, including Dragovic-Soso, are hopeful that the establishment of an ICTY archive could at least partially resolve the issues — blame-shifting and indifference — presented by the lack of a coherent historic record in the region. Among the information included would be “numbers and names of people killed; the circumstances of their deaths; [information on] detention centers and where they were located.”

Of course, Dragovic-Soso noted, a tribunal archive would deal only with those cases that were adjudicated within its legal boundaries and wouldn’t contain the experience of victims, just those convicted or acquitted.

Like many violent episodes that played out against the backdrop of the post-World War II international order, NGOs and international governmental organisations have been deeply involved in shaping the justice and reconciliation process, and come July, London will host the fifth meeting of the Berlin Process,where dealing with the ICTY’s legacy issues will be on the agenda.

A quarter century on, though, a further issue confounds such meetings. As Jelena Petrovic, Post-doctoral Research Associate in the Department of War Studies at King’s College London, asked her fellow panelists, “To what extent are we keeping the conflict alive by deciding externally what needs to be done?”.

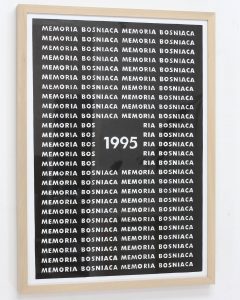

Image credit: Paul Lowe

Nora Biette-Timmons is a journalist and a masters student in Comparative Politics in the Department of Government at LSE. You can find her on Twitter: @biettetimmons.

Nora Biette-Timmons is a journalist and a masters student in Comparative Politics in the Department of Government at LSE. You can find her on Twitter: @biettetimmons.

College London. Alongside this, from 29 November – 1 December we will be holding a symposium where project participants, artists, practitioners and academics will explore the key themes of the project: What is reconciliation? What practices constitute spaces of reconciliation? What do the arts have to offer in post-conflict settings? How are we to measure the effectiveness of reconciliation interventions? To capture the eclectic and interdisciplinary nature of the project, the presentations will take on a variety of forms, from arts practice and contact improvisation workshops, keynotes, panels, exhibition walk throughs, and film screenings.

College London. Alongside this, from 29 November – 1 December we will be holding a symposium where project participants, artists, practitioners and academics will explore the key themes of the project: What is reconciliation? What practices constitute spaces of reconciliation? What do the arts have to offer in post-conflict settings? How are we to measure the effectiveness of reconciliation interventions? To capture the eclectic and interdisciplinary nature of the project, the presentations will take on a variety of forms, from arts practice and contact improvisation workshops, keynotes, panels, exhibition walk throughs, and film screenings. Isabella Pearce (MA Student in the Department of War Studies, King’s College London), reflects on the exhibition, REconciliations, and artist workshops convened by the Art&Reconciliation project. The blog post can be found

Isabella Pearce (MA Student in the Department of War Studies, King’s College London), reflects on the exhibition, REconciliations, and artist workshops convened by the Art&Reconciliation project. The blog post can be found

Nora Biette-Timmons is a journalist and a masters student in Comparative Politics in the Department of Government at LSE. You can find her on Twitter:

Nora Biette-Timmons is a journalist and a masters student in Comparative Politics in the Department of Government at LSE. You can find her on Twitter: